First of all, it's worth noting that my approach to the value of blogging for teaching and learning in Language Arts is deeply informed by the work of a number of teacher-researchers from several fields. Most notable among these are Paul Allison, whose chapter "Be a Blogger: Social Networking in the Classroom" (in Teaching the New Writing: Technology, Change, and Assessment in the 21st-Century Classroom, by Anne Herrington, Kevin Hodgson, and Charles Moran) offers a glimpse into the day-to-day workings of a blogging-focused ELA curriculum; and Sam Rose and Howard Rheingold, who have devised (and made publicly available) an enormous set of resources for teaching in and through new media platforms.

My approach is also informed by my personal experience as a blogger--really, to be fair, as someone who is willing to squeeze out nearly anything in order to make time for posting. By even my most generous estimate, I spend far too much of my time blogging--unless you account for the formative value of blogging for someone like me. I am convinced that the intellectual and identity work required for me to maintain this space has led directly to my growing prowess as a researcher, reader, and writer. You cannot convince me otherwise; so do not even bother trying.

My experiences and the reading I've done about the value of blogging for learning informs everything that comes next.

Characteristics of blogging that support new media literacy

Reaching a wide(r) reader base

It's important to note that blogs differ in purpose from many seemingly similar writing platforms. It's obvious to most that a blog is different from a personal journal, in that while many of us may hope to have our journals read by a larger public some day, blogs are actually intended to support wider readership. The majority of blogs are public (meaning anybody can view them) and taggable, and they come up as legitimate sites in web searches.

Blogs also differ from forums, chat rooms, instant message programs, and social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook. Of all of these spaces, blogs are generally the most polished, the most text-based, and the most supportive of extended engagement with a single idea.

Shifting from intended audience to intended public

This idea is ripped from Howard Rheingold, who (tapping into some Habermas) writes that

[m]oving from a private to a public voice can help students turn their self-expression into a form of public participation. Public voice is learnable, a matter of consciously engaging with an active public rather than broadcasting to a passive audience.

The move here is away from the "please read what I wrote" approach to "please act on the ideas I've written down here." The regular practice required for building and maintaining a blog's readership helps to crystallize this shift and helps writers to see there is a broad, if constantly shifting, group of people whose interests align with the broad, if constantly shifting, ideas of a blog. Though the intended public is largely invisible (we have generally only met a fraction of our blog's readers), consistent practice in finding, drawing in, and engaging this target public makes them less transparent.

Blogs as (genuine) conversations

When I taught college composition lo these many years ago, I always tried to argue to my students that all writing is a conversation--that when we write, we take up ideas that were presented by other writers before us and try to present something new that might be of interest to people who care about the kinds of things we write about.

The argument always felt hollow to me. After all, college students are typically only eavesdroppers. Only a handful of people will ever read what they've written, and often the students don't really care all that much about the assigned writing topics anyway. Add to that the artificial motivator of the ever-elusive 'A' and you have a recipe for calamity.

But blogs--now blogs are authentic communication spaces. They really are. Anybody can get almost anybody to read a blogpost and, if the post is engaging enough, to comment on the post for all eternity to see. This very fact ups the ante some: Getting the spelling of someone's name suddenly matters an awful lot. Making a concise, well supported argument has real, potential consequences: A strong enough argument gets people to sit up and notice. A strong enough argument gets people to act.

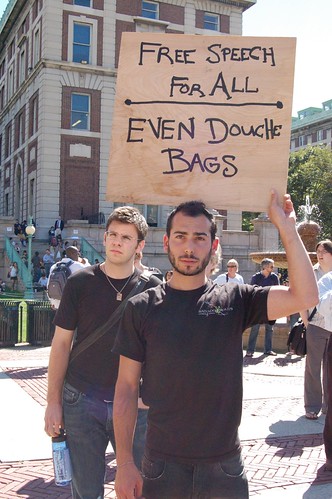

A move toward increasingly public spheres of participation

An increasingly participatory culture calls for participation that's ethical, reasoned, and publicly accessible. After all, the widespread takeup of the spirit of participatory culture requires that we all act in ways that keep the barriers to participation low, the potential for contribution high, and the mentorship possibilities readily available to most or all participants. This can only happen to the extent that all or most of us are willing to operate, to express and circulate our ideas and creative works, in public online and offline spaces. Since so much discourse will increasingly happen in public spaces, it only makes sense that we use the ELA domain to prepare students for engagement in those public spaces.

Blogs as spaces for fostering both traditional and new media literacies

For language arts teachers, blogging presents a fairly obvious avenue for preparing learners for engagement in public spheres of communication, since blogs align nicely with the traditional purposes of the ELA classroom. As a group of readers engage in deep analysis of their own and others' blogs, they have to think about issues like tone, style, genre, punctuation, word choice, and organization.

The extra toy prize is that students also get to learn about the characteristics of online writing, including what danah boyd identifies as the four properties of online communication (persistence, searchability, replicability, and scalability) and three dynamics (invisible audiences, collapsed contexts, and the blurring of public and private). As my colleague Michelle Honeyford put it, "they hit all the standards and get to learn about online participation for free."

Confronting the ethics challenge

Nobody's arguing that we should sign every sixth grader up with a Blogger account. That would just be silly. Media scholar Henry Jenkins is fond of saying that the role of educators and parents is not to look over kids' shoulders but to watch their backs, and scaffolding learners toward participation in increasingly public spheres allows us to do just that. Lots of teachers (including the famously brilliant Becky Rupert at Bloomington's Aurora Alternative High School) start their students out by having them post to a private space (she uses Ning) but having them analyze writing from more public spaces. This way, they have a kind of new media sandbox to try out and engage with the norms of online communication before actually being held to the higher ethical standard, with deeper potential repercussions (both positive and negative).

That's all I have for now, though I would love to hear from you on the list above. What have I missed? What am I ignoring? What struggles are linked to bringing blogs into the classroom, and what challenges have you encountered if you've tried to do so?

I hope for this to be a multipart post that will include thoughts on the following categories:

- Affordances of blogging as a new media writing technology

- Challenges to integrating blogs into the ELA classroom

- Resources (including lesson plans, other writing on this topic, etc.)

- Assessment guidelines for working with blogs

If you have thoughts on any of the above, I'd love to hear from you. If you have any trouble posting comments (I don't know why, but some of you have) please email me at jennamcjenna(at)gmail(dot)com.