The first was Petty Officer Edgar Evans, who had suffered extreme frostbite and wandered away from camp. Scott wrote:

I was first to reach the poor man and shocked at his appearance; he was on his knees with clothing disarranged, hands uncovered and frostbitten, and a wild look in his eyes. Asked what was the matter, he replied with a slow speech that he didn't know, but thought he must have fainted. We got him on his feet, but after two or three steps he sank down again. He showed every sign of complete collapse. Wilson, Bowers, and I went back for the sledge, whilst Oates remained with him. When we returned he was practically unconscious, and when we got him into the tent quite comatose. He died quietly at 12.30 A.M. On discussing the symptoms we think he began to get weaker just before we reached the Pole, and that his downward path was accelerated first by the shock of his frostbitten fingers, and later by falls during rough travelling on the glacier, further by his loss of all confidence in himself. Wilson thinks it certain he must have injured his brain by a fall.

The second to die was Captain Titus Oates, who suffered such extreme physical deterioration as a result of severe frostbite, hunger, and exhaustion that he was nearly completely unable to walk. In the end he was such a burden to the other members of the expedition that he asked to be left behind. Here's how Scott's diary describes Oates's final hours:

Should this be found I want these facts recorded. Oates' last thoughts were of his Mother, but immediately before he took pride in thinking that his regiment would be pleased with the bold way in which he met his death. We can testify to his bravery. He has borne intense suffering for weeks without complaint, and to the very last was able and willing to discuss outside subjects. He did not - would not - give up hope till the very end. He was a brave soul. This was the end. He slept through the night before last, hoping not to wake; but he woke in the morning - yesterday. It was blowing a blizzard. He said, 'I am just going outside and may be some time.' He went out into the blizzard and we have not seen him since... We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit, and assuredly the end is not far....

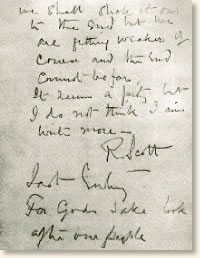

When an expedition discovered Scott's body, along with those of his companions Lieutenant Henry Bowers and Dr. Edward Wilson, they also recovered Scott's diary. A copy of the last page, with a translation, is included below.

We shall stick it out

to the end, but we

are getting weaker, of

course, and the end

cannot be far.

It seems a pity, but

I do not think I can

write more.R. ScottLast entry

For God's sake look

after our people.